All mountaineers are eventually asked...

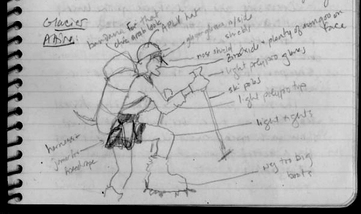

Glacier attire, from Makalu journal. September - October 1998. Makalu, Nepal

Glacier attire, from Makalu journal. September - October 1998. Makalu, Nepal ...why do you climb mountains? Mallory, contrary to popular myth ("Because it's there"), said,

"What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy... That is what life means and what life is for."

Why do I climb mountains?

Because I can stand next to my tent in the crisp early morning light and both see and feel the mountain above me, the fluted ridges, the brilliant snow. It is a palpable presence.

I can feel a connection to the mountain, basal, spiritual, gut-wrenching. Deep.

I can feel the age of the mountain, the ancient stones, the millennia witnessed. I feel young and naive.

I can feel the mass of the mountain sinking deep into the earth. I feel light, a feather floating over the earth. I know myself better through this connection.

David and I gear up for moving over snow. The Polish-American team is do-si-do-ing all over the upper reaches of the route on Makalu. I can practically hear the fiddle and the banjo setting the tempo of the day. Rysiek and Piotr are coming down from having set up Camp 3 at Makalu La, 7,300m. Chris and Jacek are moving up to the new digs. Kryszek and Josek are resting at Camp 2. Tomorrow they'll move up to the La. David and I are moving up from Camp 1 to join them at Camp 2 and then we'll take our turn at the La.

It's hot. David points out that, by his little thermometer zipper pull, it's as hot here as it was down in the jungle when we trekked in. Ugh. I'm sweating bullets. Going up, I move slowly, gasping for air. Where's the strength? What's the point of having strong legs if you can't get oxygen to them? I look around. David's gasping too. The Korean team is only moving a little faster than me. OK, but I feel like shit. It's a beautiful day, the mountains around us are crisp. But my lungs are too small.

Crevasses are strung with ropes fixed across them. I pick up the rope, clip the ascender onto it, and watch my feet as I approach the flags marking the crevasse crossing. I look into the smooth, yawing blue depths of the crevasse and feel the adrenaline thrill of the "what-if", then jump across it, and silently thank the sherpas who fixed the route for the Japanese. The steep faces of the seracs are also fixed with ropes. It's a relief to finally use my arms instead of only legs as I work my way up these faces.

Piotr and Rysiek stop on their descent to Base Camp to chat with us, happy to be going down after being at 7,300m. There aren't many mountaineers of their caliber. Anywhere. Of their peers, few are as personable. There are plenty of prima-donnas in the circle of great mountaineers. But not these two.

Why do I climb mountains?

Because of the feeling of family and community in the group, the shared desires, the shared experiences, the understanding--unspoken--in the the beauty of every vista, every move, every connection between body and mountain. The people who choose this lifestyle are independent, rugged, free... yet full of individuality, expression, and weirdness. It seems the mountains unveil the raw person, naked and full of character. Beautiful, strange, hung-up, fancy-free, solemn, honest in the passion that drew them here in the first place.

By the last of the three steep pitches it has begun to snow lightly. We finally arrive at Camp 2, and I am exhausted. My head is pounding. Josek and Kryszek have made us Tang and tea. Amazing. We drink it up. I realize I've eaten and drunk almost nothing all day. By now the snow is serious and the wind is picking up, so we throw our packs in the vestibule say good bye to the men and dive for the tent.

Then I throw up all that nice Tang and tea.

By now I've had a little practice with my pee bottle, so at least my aim is good and I don't make a colorful mess on the tent floor. I hand the radio over to David and roll over in my sleeping bag to have some private time with my physical misery. 6,380m. An all-time elevation record. Whoop-dee-do.

Why do I climb mountains?

This headache follows me like a shadow. It throbs when I move my head suddenly or step heavily on a rock. My lungs are so crammed into my chest with my heart that they can't both function at the same time - its air or blood, take your pick. My stomach is on the edge of nausea, so that the thought of food any heavier than soup makes me queasy. My muscles burn for oxygen. I feel cheated, like I've lost my intimacy with my own body. A simple few steps down the ridge to pee take an inordinate amount of pain and energy to retrace. My throat is constantly raw, my lips cracked.

In the interstices between nausea and sleep, I meditate on better memories from the lower reaches of the mountain...

After breakfast, the porters slip into mountainous packs. A few of us climbers do the same and follow them. The way to Advanced Base Camp is cryptic in the tallus of the receding glacier. The porters skip up the route. The lead man flaps his arms, spins in circles and sings. He seems ecstatic to be leading our troupe up the mountain. I admire him.

The route leaves Base Camp at 4,600 m and follows the river up sandy trail, easy. Then it climbs the lateral moraine of the glacier that feeds the river. We change to boulder-hopping. Most of the rocks stay put. The leader is dancing from rock to rock, still singing, as easy to keep up with as a rainbow. The route skirts around the western side of Makalu, under the prow of the West Pillar, but the mountain itself is obscured in the clouds.

A waterfall, a ribbon of water cascading thousands of feet from the tongue of a hanging glacier across the valley, stops me short. I notice a cave used by climbers over many generations. I walk inside and see old fire rings and fortified walls, see where sleeping areas had been scraped flat, and wonder at the universality of comfort in a warm fire. How old this place is, this way of life.

Why do I climb mountains?

In a tallus field, to jump from boulder to boulder, to know where to put one's foot, where to land one's weight, how to balance the body so as not to move a stone, and to flow naturally, without effort, on to the next boulder... This approaches perfection. This is to know the mountain. This is to interact with it perfectly, with understanding and respect.

I drift off to sleep remembering...

"What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy... That is what life means and what life is for."

Why do I climb mountains?

Because I can stand next to my tent in the crisp early morning light and both see and feel the mountain above me, the fluted ridges, the brilliant snow. It is a palpable presence.

I can feel a connection to the mountain, basal, spiritual, gut-wrenching. Deep.

I can feel the age of the mountain, the ancient stones, the millennia witnessed. I feel young and naive.

I can feel the mass of the mountain sinking deep into the earth. I feel light, a feather floating over the earth. I know myself better through this connection.

David and I gear up for moving over snow. The Polish-American team is do-si-do-ing all over the upper reaches of the route on Makalu. I can practically hear the fiddle and the banjo setting the tempo of the day. Rysiek and Piotr are coming down from having set up Camp 3 at Makalu La, 7,300m. Chris and Jacek are moving up to the new digs. Kryszek and Josek are resting at Camp 2. Tomorrow they'll move up to the La. David and I are moving up from Camp 1 to join them at Camp 2 and then we'll take our turn at the La.

It's hot. David points out that, by his little thermometer zipper pull, it's as hot here as it was down in the jungle when we trekked in. Ugh. I'm sweating bullets. Going up, I move slowly, gasping for air. Where's the strength? What's the point of having strong legs if you can't get oxygen to them? I look around. David's gasping too. The Korean team is only moving a little faster than me. OK, but I feel like shit. It's a beautiful day, the mountains around us are crisp. But my lungs are too small.

Crevasses are strung with ropes fixed across them. I pick up the rope, clip the ascender onto it, and watch my feet as I approach the flags marking the crevasse crossing. I look into the smooth, yawing blue depths of the crevasse and feel the adrenaline thrill of the "what-if", then jump across it, and silently thank the sherpas who fixed the route for the Japanese. The steep faces of the seracs are also fixed with ropes. It's a relief to finally use my arms instead of only legs as I work my way up these faces.

Piotr and Rysiek stop on their descent to Base Camp to chat with us, happy to be going down after being at 7,300m. There aren't many mountaineers of their caliber. Anywhere. Of their peers, few are as personable. There are plenty of prima-donnas in the circle of great mountaineers. But not these two.

Why do I climb mountains?

Because of the feeling of family and community in the group, the shared desires, the shared experiences, the understanding--unspoken--in the the beauty of every vista, every move, every connection between body and mountain. The people who choose this lifestyle are independent, rugged, free... yet full of individuality, expression, and weirdness. It seems the mountains unveil the raw person, naked and full of character. Beautiful, strange, hung-up, fancy-free, solemn, honest in the passion that drew them here in the first place.

By the last of the three steep pitches it has begun to snow lightly. We finally arrive at Camp 2, and I am exhausted. My head is pounding. Josek and Kryszek have made us Tang and tea. Amazing. We drink it up. I realize I've eaten and drunk almost nothing all day. By now the snow is serious and the wind is picking up, so we throw our packs in the vestibule say good bye to the men and dive for the tent.

Then I throw up all that nice Tang and tea.

By now I've had a little practice with my pee bottle, so at least my aim is good and I don't make a colorful mess on the tent floor. I hand the radio over to David and roll over in my sleeping bag to have some private time with my physical misery. 6,380m. An all-time elevation record. Whoop-dee-do.

Why do I climb mountains?

This headache follows me like a shadow. It throbs when I move my head suddenly or step heavily on a rock. My lungs are so crammed into my chest with my heart that they can't both function at the same time - its air or blood, take your pick. My stomach is on the edge of nausea, so that the thought of food any heavier than soup makes me queasy. My muscles burn for oxygen. I feel cheated, like I've lost my intimacy with my own body. A simple few steps down the ridge to pee take an inordinate amount of pain and energy to retrace. My throat is constantly raw, my lips cracked.

In the interstices between nausea and sleep, I meditate on better memories from the lower reaches of the mountain...

After breakfast, the porters slip into mountainous packs. A few of us climbers do the same and follow them. The way to Advanced Base Camp is cryptic in the tallus of the receding glacier. The porters skip up the route. The lead man flaps his arms, spins in circles and sings. He seems ecstatic to be leading our troupe up the mountain. I admire him.

The route leaves Base Camp at 4,600 m and follows the river up sandy trail, easy. Then it climbs the lateral moraine of the glacier that feeds the river. We change to boulder-hopping. Most of the rocks stay put. The leader is dancing from rock to rock, still singing, as easy to keep up with as a rainbow. The route skirts around the western side of Makalu, under the prow of the West Pillar, but the mountain itself is obscured in the clouds.

A waterfall, a ribbon of water cascading thousands of feet from the tongue of a hanging glacier across the valley, stops me short. I notice a cave used by climbers over many generations. I walk inside and see old fire rings and fortified walls, see where sleeping areas had been scraped flat, and wonder at the universality of comfort in a warm fire. How old this place is, this way of life.

Why do I climb mountains?

In a tallus field, to jump from boulder to boulder, to know where to put one's foot, where to land one's weight, how to balance the body so as not to move a stone, and to flow naturally, without effort, on to the next boulder... This approaches perfection. This is to know the mountain. This is to interact with it perfectly, with understanding and respect.

I drift off to sleep remembering...

- Nepalese women reaching to touch the good luck beads on my necklace, smiling with both approval and understanding.

- Jacek asking what's in the leather pouch around my neck. My hopes and dreams, I reply, and the support of my closest friends.

- Chris posing for a Moonstone shot in the tent. I commented on how she's a Moonstone slut and I'm a North Face slut. What does that make me? Jacek (sponsored by Alpinus) demands. The question was left open.

- My camera fails to rewind. Everyone has a go, but its no use. I have to open it up. It got wet with a chest-high river fording and all the film is stuck together. I bring the trailing roll of ruined film to the mess tent after the operation and point out to Josek a particularly good shot of him on the way to Camp 1. Kryszek suggests we rewind the roll and sell it to the recently arrived Korean team.

From journal entries. September-October 1998. Standard French Route, Makalu, Nepal Himalaya