The road up Whiteface ducks in and out of stream valleys as it makes its way up the northwest side of the mountain. The ascent is gradual and, on a day like this in the middle of winter, spectacularly beautiful. The Adirondack peaks of St. Regis, Catamount, and Lyon Mt. to the north are made all the more austere by the snow. Crags and ice are visible. Everything is black and white. On the other side of me, Whiteface rises above the road to the skyline, defined by black conifers mantled in white snow. This side of the mountain sees the winter sun four hours on a good day. It is rarely warm here.

This is my commute. At a site roughly halfway, or four miles, up this road I sample red spruce foliage for Boyce Thompson Institute, to figure out how these trees are damaged by winter. Today I'm hitching a ride up the mountain with the head of operations at the Atmospheric Sciences Research Center, on the back of a snowcat. Snowcats and snowmobiles are the only vehicles that can make it up this road in the winter. After the recent storm, though, even a snowmobile would wallow in the fresh powder on the road. The snowcat is belching gas fumes and roaring with a steady grumble. My dog refused to be coaxed onto the rear platform, dancing out of reach, staying clear of this deafening and noxious monster. So, with a shrug, I clambered aboard and signaled Doug to go anyway. We lurched up the road as gracefully as an adolescent dinosaur.

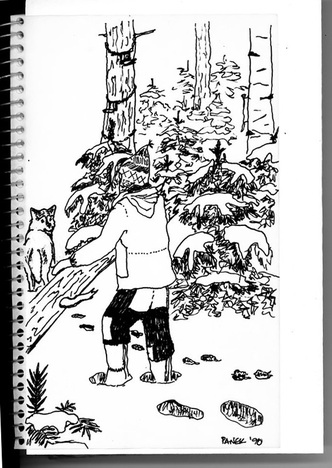

As we climb, the northern hardwood forest gives way to the spruce, fir and birch zone where I work. My dog zags across our tracks in great lumbering leaps, her tongue out, her chest heaving in an attempt to keep up. Doug stops and asks if she's ready to ride. She is. I'm as grateful as she is, though, when the ride is over. I unload skis and pack and slip into the cover of the forest. The gasoline fumes cling to me, they will for days, but at least the roar recedes into the distance.

The last time I sampled here was September and the place has been transformed. Where once I was able to duck under young fir, now the deep snowpack I'm standing on makes me a full head taller than them. I step over fallen trees I used to walk under. The canopy of birch leaves is now gone and I'm able to see through their branches to the mature spruce and fir towering over me. Everything is encased in a sheath of snow and rime ice. A wind is up, it spits snow in my face and despite the many layers of clothes I have on, the mittens and the hat, I feel very cold. I regret needing to take off my mittens, but I have to buckle into my safety harness. I turn on the 2-way radio (walkie-talkie) and call down to base. Everything's fine, I'm ready to climb trees.

Each tree has its own "personality", as different as people can be. I can identify trees by many means - bark texture, shoot length, needle shape, branching pattern of limbs - but its this latter that is most evident now, under icy conditions. The benign and "friendly" trees are easy to climb. They have branches at regular intervals, sticking straight out from the trunk. The "malicious" trees have downward sloping branches that are a challenge to stand on, or branches that are spaced so far apart that I have to stretch precariously to reach and climb to a clump above me. I'm constantly aware of the placement of my feet. All the training I've had as a rock climber comes to bear here, moving upward forty feet above the ground in a spruce on a snowy winter day.

The task of clipping and Zip-locking foliage while in a tree requires the dexterity of all fingers. After shaking snow loose from a branch and locating a suitable sample, the mittens come off. As soon as fingers numb from the cold, Zip-locs become IQ tests, I become miserably incompetent, and the mittens go back on. While I wait for my hands to warm, I take in my surroundings and absorb the beauty of the view. I can see the summit arete above me, rock plastered with ice, sometimes disappearing behind a veil of driving snow and cloud. The valley below is a mosaic of textures - sharp, black conifers; frozen and flat matte-white lakes; smooth, rounded hills covered in powder.

I return to the ground and to a greeting from my dog as warm as if I'd been gone for days. She frets over me like a grandmother. We romp for a moment in the snow, then I put on my most business-like voice and radio down to the base-station support that all is well. We romp for a minute more before I tackle the next tree.

When all is finished, I commute back down the mountain road on my skis. Most of the way, the smooth ride lulls me into daydreaming. But a windswept patch catches me unawares, the pavement grabs at my skis and throws me to the ground amid a shower of sparks from my metal edges. The commuter train derailed.

I enjoy the contrast between the world high in a spruce on a bitter, winter day and that of the sterile chemical lab where I process my samples just four miles below. Environmental science incorporates both worlds, the natural and the man-made, the physical and the cerebral. I'm fortunate that my job bridges both.

This is my commute. At a site roughly halfway, or four miles, up this road I sample red spruce foliage for Boyce Thompson Institute, to figure out how these trees are damaged by winter. Today I'm hitching a ride up the mountain with the head of operations at the Atmospheric Sciences Research Center, on the back of a snowcat. Snowcats and snowmobiles are the only vehicles that can make it up this road in the winter. After the recent storm, though, even a snowmobile would wallow in the fresh powder on the road. The snowcat is belching gas fumes and roaring with a steady grumble. My dog refused to be coaxed onto the rear platform, dancing out of reach, staying clear of this deafening and noxious monster. So, with a shrug, I clambered aboard and signaled Doug to go anyway. We lurched up the road as gracefully as an adolescent dinosaur.

As we climb, the northern hardwood forest gives way to the spruce, fir and birch zone where I work. My dog zags across our tracks in great lumbering leaps, her tongue out, her chest heaving in an attempt to keep up. Doug stops and asks if she's ready to ride. She is. I'm as grateful as she is, though, when the ride is over. I unload skis and pack and slip into the cover of the forest. The gasoline fumes cling to me, they will for days, but at least the roar recedes into the distance.

The last time I sampled here was September and the place has been transformed. Where once I was able to duck under young fir, now the deep snowpack I'm standing on makes me a full head taller than them. I step over fallen trees I used to walk under. The canopy of birch leaves is now gone and I'm able to see through their branches to the mature spruce and fir towering over me. Everything is encased in a sheath of snow and rime ice. A wind is up, it spits snow in my face and despite the many layers of clothes I have on, the mittens and the hat, I feel very cold. I regret needing to take off my mittens, but I have to buckle into my safety harness. I turn on the 2-way radio (walkie-talkie) and call down to base. Everything's fine, I'm ready to climb trees.

Each tree has its own "personality", as different as people can be. I can identify trees by many means - bark texture, shoot length, needle shape, branching pattern of limbs - but its this latter that is most evident now, under icy conditions. The benign and "friendly" trees are easy to climb. They have branches at regular intervals, sticking straight out from the trunk. The "malicious" trees have downward sloping branches that are a challenge to stand on, or branches that are spaced so far apart that I have to stretch precariously to reach and climb to a clump above me. I'm constantly aware of the placement of my feet. All the training I've had as a rock climber comes to bear here, moving upward forty feet above the ground in a spruce on a snowy winter day.

The task of clipping and Zip-locking foliage while in a tree requires the dexterity of all fingers. After shaking snow loose from a branch and locating a suitable sample, the mittens come off. As soon as fingers numb from the cold, Zip-locs become IQ tests, I become miserably incompetent, and the mittens go back on. While I wait for my hands to warm, I take in my surroundings and absorb the beauty of the view. I can see the summit arete above me, rock plastered with ice, sometimes disappearing behind a veil of driving snow and cloud. The valley below is a mosaic of textures - sharp, black conifers; frozen and flat matte-white lakes; smooth, rounded hills covered in powder.

I return to the ground and to a greeting from my dog as warm as if I'd been gone for days. She frets over me like a grandmother. We romp for a moment in the snow, then I put on my most business-like voice and radio down to the base-station support that all is well. We romp for a minute more before I tackle the next tree.

When all is finished, I commute back down the mountain road on my skis. Most of the way, the smooth ride lulls me into daydreaming. But a windswept patch catches me unawares, the pavement grabs at my skis and throws me to the ground amid a shower of sparks from my metal edges. The commuter train derailed.

I enjoy the contrast between the world high in a spruce on a bitter, winter day and that of the sterile chemical lab where I process my samples just four miles below. Environmental science incorporates both worlds, the natural and the man-made, the physical and the cerebral. I'm fortunate that my job bridges both.

A BTI sketchbook of everyday lives. In, The Expression Vector 2(4), Boyce Thompson Institute of Plant Research. Newsletter, April 1990.